The Ground Wire

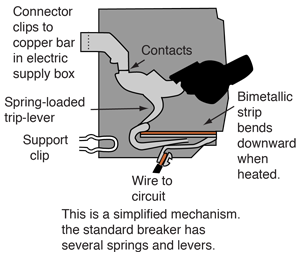

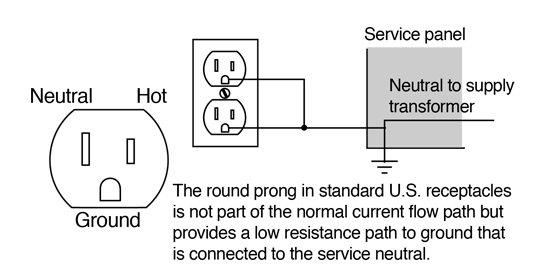

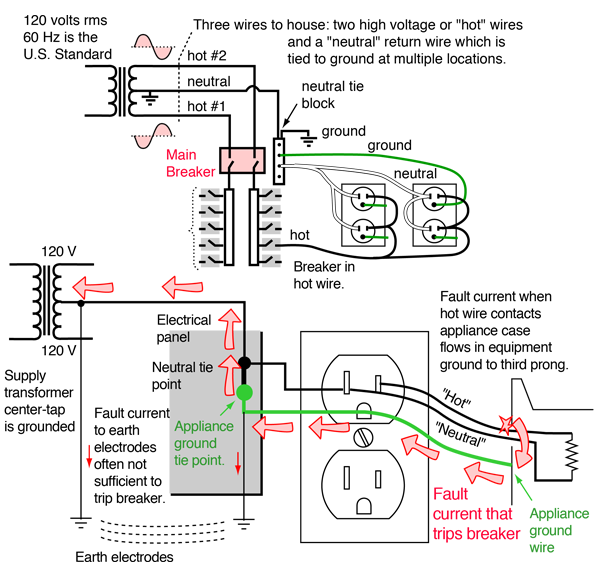

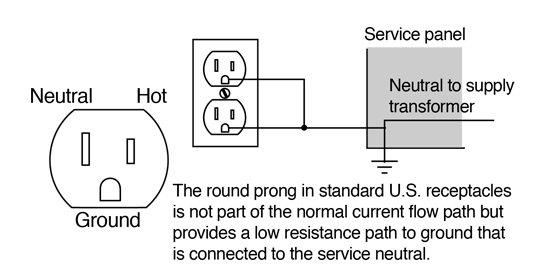

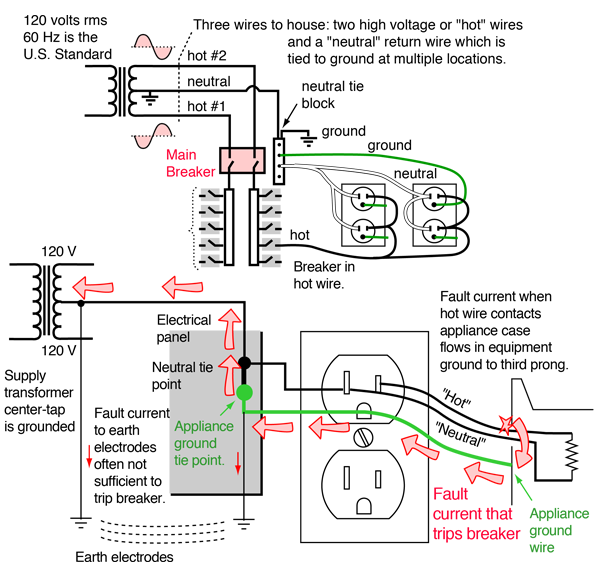

The term "ground" refers to a connection to the earth, which acts as a reservoir of charge. A ground wire provides a conducting path to the earth which is independent of the normal current-carrying path in an electrical appliance. As a practical matter in household electric circuits, it is connected to the electrical neutral at the service panel to gaurantee a low enough resistance path to trip the circuit breaker in case of an electrical fault (see illustration below). Attached to the case of an appliance, it holds the voltage of the case at ground potential (usually taken as the zero of voltage). This protects against electric shock. The ground wire and a fuse or breaker are the standard safety devices used with standard electric circuits.

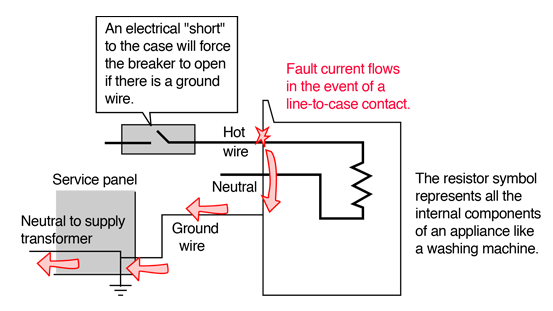

Is the ground wire necessary? The appliance will operate normally without the ground wire because it is not a part of the conducting path which supplies electricity to the appliance. In fact, if the ground wire is broken or removed, you will normally not be able to tell the difference. But if high voltage has gotten in contact with the case, there may be a shock hazard. In the absence of the ground wire, shock hazard conditions will often not cause the breaker to trip unless the circuit has a ground fault interrupter in it. Part of the role of the ground wire is to force the breaker to trip by supplying a path to ground if a "hot" wire comes in contact with the metal case of the appliance.

In the event of an electrical fault which brings dangerous high voltage to the case of an appliance, you want the circuit breaker to trip immediately to remove the hazard. If the case is grounded, a high current should flow in the appliance ground wire and trip the breaker. That's not quite as simple as it sounds - tying the ground wire to a ground electrode driven into the earth is not generally sufficient to trip the breaker, which was surprising to me. The U.S. National Electric Code Article 250 requires that the ground wires be tied back to the electrical neutral at the service panel. So in a line-to-case fault, the fault current flows through the appliance ground wire to the service panel where it joins the neutral path, flowing through the main neutral back to the center-tap of the service transformer. It then becomes part of the overall flow, driven by the service transformer as the electrical "pump", which will produce a high enough fault current to trip the breaker. In the electrical industry, this process of tying the ground wire back to the neutral of the transformer is called "bonding", and the bottom line is that for electrical safety you need to be both grounded and bonded.

This just touches the tip of the iceberg of the major subject of proper grounding and bonding of electrical systems. See Mike Holt's site for further information.

|

Index

Practical circuit concepts

Mike Holt |